Ephesians 4:25-29 Have you ever watched a flock of crows leave a tree, suddenly, altogether, responding to some alarm or desire that sends them all straight up in the air and then, like a wave, they rush away, and then swirling together as the most talented dance troupe, until you see them come to rest as one in a nearby tree? Virginia Woolf watched rooks out her window, and noticed that they looked like “a vast net with thousands of black knots in it, cast up into the air; which, after a few moments sank slowly down upon the trees until every twig seemed to have a knot at the end of it. Then, suddenly, the net would be thrown into the air again in a wider circle this time, with the utmost clamour and vociferation, as though to be thrown into the air and settle slowly down upon the tree tops were a tremendously exciting experience.” Virginia Woolf captures with impish eloquence a scene that has captivated most of us, when we’re blessed and astounded to be walking under or driving past the tree from which hundreds of birds suddenly emerge. Bird flocks have the coolest names: a flutter of sparrows, or a murmuration of starlings, or a chime of wrens, or a squabble of gulls. We give bird flocks these evocative names because their collective identity is as important as their individual identity. Birds in groups need their own names. What Virginia Woolf saw was one vast net with thousands of black knots in it – one net, not thousands of birds. We see the same group behavior in a school of fish, or more specifically, a fleet of bass, a battery of barracudas, and a company of angel fish. A school of fish moves as one creature, swirling around coral, darting away from a shark, diving into dinner. Colonies of ants and swarms of bees are so skilled at collective identity and group consciousness that they give us hope for our own societies. Social scientists study ants and bees looking for tips that we humans can use to give our own families and cities and countries more harmony and shared vision.

1 Comment

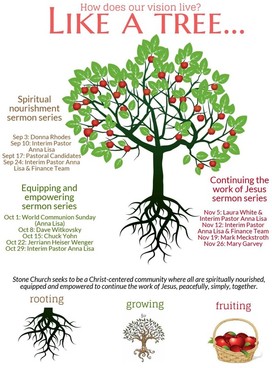

One: The Psalmist sings: All: Vindicate me, O Lord, for I have walked in my integrity, and I have trusted in the Lord without wavering. One: Perhaps some of us can claim to trust in the Lord without wavering, but most of us walking the path of trust do occasionally stumble, or lose our way All: Here we come to find our balance, to check the map, and to step back onto the path of trust One: Here we gather to seek out the path of integrity All: Here we step together into change, in our church, in our towns, in our country, in our world One: We walk together, throughout all change, we are walking together, and we are walking with God All: For your steadfast love is before our eyes, Holy One and we walk in faithfulness to you. Amen. In Pastor Christy’s last month here, some of you asked me, “How are you feeling about this transition?” If you’re new to Stone you may have heard by now that after 18 years of stable, loving leadership, Pastor Christy retired last Sunday. So last month when some of you asked how I was doing with solo pastoring Stone Church in this time of transition, I realized that I felt curious, intrigued about how we would turn this corner. I felt committed to facilitating a hearty and healthy goodbye. Consciously I wasn’t feeling anxious or worried. But I had a few nightmares in August. In each of these nightmares I would arrive at church on a Sunday morning and many things were going wrong. Usually I was late, sometimes I didn’t have church-appropriate clothes to wear, sometimes I couldn’t find my sermon. And in each of these nightmares I would come into the sanctuary and it didn’t look the same, it was usually bigger, like a huge old theatre with balconies. And the people were different. The people reading scripture or speaking were people I’d never met. I had this sort of nightmare three or four times in August, usually on a Saturday night, so when I woke up it actually was Sunday morning. And I’d come here, and happily greet this familiar sanctuary. And as you walked in I’d be grateful that we are not strangers, even though we are a changing church. As Discovery Team listened and discerned and developed our vision/mission, Stone Church continued a process of transformation. “Be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God” wrote Paul to the church in Rome. Stone Church seeks a renewing of our minds, discerning God’s call, through Vital Ministry Journey, the strategic planning that was part of the building renovations, the discernment that produced our welcoming statement. There are many more examples of when Stone Church has been intentional about learning and listening – who are we and who is God calling us to be? You have asked, and you will ask it again! We are a changing church, because church is changing in general, throughout our country and world. We are a changing church because we’re in pastoral transition. We are a changing church because each of you change personally, and because the people who gather as Stone Church are a different group of people each time. And throughout all this change we celebrate the vision/mission, our current way of discerning God’s call for Stone Church, and we are all invited into a renewing of our minds throughout this fall as we hear a variety of voices preach on the themes of our vision and mission. In September we focus on the roots – spiritual nourishment. October we’ll focus on equipping, empowering and growing in community. In November we’ll focus on bearing fruit as we continue the work of Jesus. How does our vision live? Like a tree, with well nourished roots, with a strong trunk and branches, and with abundant fruit to share with all, to continue the cycle of life. |

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed