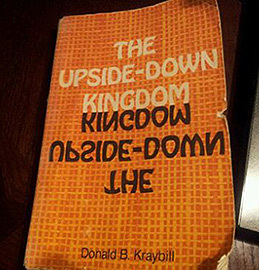

Luke 7:36-50 "...Jesus is dining at the home of a Pharisee, and Pharisees, in these days, are religious rock-stars, they are dedicated to righteous living, robust faith, rigorous devotion. In the right-side-up world, they are the righteous. And in our story from Luke, who is righteous? The sinner. I don't want to overstate the point, Jesus doesn't turn the world upside down to say that sinning is now righteous. She isn't righteous simply because she is a sinner. She is righteous because this sinful woman kneels before Jesus and weeps, and washes and anoints his feet. We might condemn her too! We've heard this story before so the shock factor has worn off. But if this happened in our living rooms, wouldn't we freak out? A woman people look down on shows up and kneels at the feet of someone we admire, starts crying, begins washing his feet and rubbing her hair on them? I think we'd be embarrassed, totally uncomfortable, confused about what this means and what's going to happen next. Well, maybe we wouldn't be as shocked as this Pharisee, cause we do feetwashing! Of course, so does this Pharisee, but presumably in the traditional way of 1st century Palestine – when a male guest comes over, the slaves wash his feet. Or the wife or daughters of the male head of house might wash the guest's feet. It's a sign of hospitality, and this Pharisee doesn't arrange for it so when this unnamed woman shows up and washes Jesus' feet, the Pharisee could be grateful that she is fixing his hospitality faux pas. But he's too upset to be grateful. Because feetwashing at that time was only about the person whose feet are being washed. The one doing the washing is invisible, just a slave or a woman of the house – the point is to honor the male guest. But everything changes with Jesus, the upside-down king, who makes feetwashing an honor for everyone involved. Jesus kneels to wash someone's feet and remember how upset Peter gets? And for 2000 years many people who follow Jesus have been challenging ourselves to kneel and wash someone's feet. And we've been dealing with the discomfort of someone else kneeling to wash our feet. We do it because Jesus tells us to do it. And maybe Jesus got the idea from this woman who did it first. In the upside-down kingdom of God we find that kneeling brings us the highest standing. The last shall be first, and the first shall be last. The ones who try to sit at the best seat at the table will lose their seat altogether. The meek shall inherit the earth. That's not good news for the Pharisee, who has been sitting in the good seat, who lives as a first, at least relative to other Jews. Is it good news for you? How are you a first? How are you a last? Just by living in this country, we live as firsts. In this community, many of us live as firsts through white privilege, education, access to health care, and wealth – at least relative wealth, not worrying where our next meal will come from, many of us live as firsts in these ways. Many of us live as firsts because we have citizenship documents, because we can use the bathroom without fear, because we can hold hands with the person we love, because we can get pulled over without panicking. Not all of us. But we each have ways that we lives as firsts. So what does it mean to be first and also seeking the upside-down kingdom of God where the first shall be last and the last shall be first? We turn to this story of the woman who does a beautiful thing. She brings her whole self to Jesus' feet. She knows what people say about her. She is called "sinful woman" rather than called by her own name. She weeps – wouldn't you? Haven't you, when you've lived with shame? When you've been called out of your name? Upside-down king Jesus doesn't want us to show up in our Sunday best and show off our righteousness through boastful prayers or loud demonstrations of our wealth and power. He rejects that behavior over and over. Jesus looks for the short thief climbing the tree, Jesus loves the little children, Jesus blesses the blind, the begging, the bleeding. She anoints him king of an upside-down kingdom where first shall be last and last shall be first. Where we each take our turn to kneel at another's feet and we each take a turn to watch someone kneel and wash our feet, and then we rise as equals in the upside-down kingdom. A kingdom where our righteousness comes not from pure and perfect living, but from pouring ourselves out in vulnerability and love. This upside-down kingdom is all around us, as we strive to usher in God's kingdom working for justice, seeking peace, striving for equality. We're singing about turning the world upside-down with God in the hymn My soul cries out this morning. That's the upside-down kingdom around us. And this upside-down kingdom is also within us, in the way we know our own worth, in the way we relate to our own strengths and weaknesses, successes and failures, in the way we understand ourselves as first or last. And we can usher in this upside-down kingdom inside ourselves right now, even when the world outside us seems as violent and cruel and unjust as ever. Even now, when the world seems as out of control, as far from God's kingdom as ever. We can usher in the upside-down kingdom inside ourselves when we overturn our values to look like Jesus' values. Jesus praises this woman's faith, praises her service, calls her behavior beautiful when she seeks him out, in a place where she will be snubbed. She risks rejection because she chooses to value her own soul, her own healing, more than what others will say about her. She pours her whole self out to him. She turns her weakness into strength as she cares for him. Her vulnerability is true ability, as she washes his feet, anoints him king, blesses him beautifully. This is the paradox of faith, often the paradox of healing. When we let go of denial, when we stop hiding, when we step into the harsh light and are seen for who we are, there is nothing left to fear. We have found our way back to ourselves and it is the most beautiful thing, to be known.

2 Comments

John 16:12-15 Sermon snippets ...Israelite altars, like many other cultures’ altars, were a place to sacrifice and burn animals and other food. By burning the food, the smoke took the food to God so that the people could share a meal with God. This ritual bridged the mysterious chasm between people and God through smoke’s ability to be both here and beyond – isn’t that beautiful? We can make a mistake, when we look back at our faith ancestors, of thinking them superstitious or silly. Sharing a meal with God through smoke that is both here and beyond is profound. For thousands of years Israelites built altars throughout the Holy Land, we read of Abraham and Jacob and Moses building altars to mark places they encountered God. But the Israelites were often nomadic, and they longed to feel God’s presence with them always and everywhere, so they made a traveling home for God, the Tabernacle, where they kept the Ark of the Covenant. And once the people settled down, God settled down too. And they built the Temple. It was destroyed and rebuilt, and the Temple was the bridge to God for centuries. The edges of the Temple were available to anyone, to non-Jews. Next were places only Jews were allowed. Then only men were allowed. Then only priests were allowed. Finally, only the High Priest was allowed into the Holy of Holies, the inner chamber of the Temple that was God’s home. It seems like a paradox, but in order for the people to have the connection they wanted to have to God, they developed, or at least abided by, a system in which the fewer people who could approach God, the more God’s holiness was honored. But always there’s a tension between embracing God’s mysterious, ethereal nature, and longing to embrace God. This God who had taken the form of angels, a burning bush, ferocious storms, was now brought close through a special home in the Temple. This place was an ultimate bridge to God, mediated by the High Priest, who himself was another bridge to God. But what happens when we get too attached to the bridges? Could we focus so much on the bridge that we end up farther away from God? Time after time, the bridges we build to get close to God become boundaries. The absolute mystery of the Divine is hopelessly ethereal, so we build sturdy, intricate bridges. But these bridges are not God, and these bridges will inevitably fail. Temple priests might be corrupt. Contemporary priests might abuse children. Temples can be destroyed. No bridge to God is eternal, but God is eternal. Any bridge can become a boundary. Conflict over who the Pope is can become a war. Conflict over who gets to be priests and pastors, who gets to bridge us to God, splits churches. Rituals, theology, prayer, the work of the church, are bridges to God. Some are complicated like the Catholic rosary, and its complexity reminds us how impossible it is to encapsulate God. But some of us will eventually forget that God is the point, not the ritual or words. The energy we spend on determining the “right” way to practice rituals or understand theology or pray can leave us feeling farther from God than ever, and our bridges become boundaries. God is beyond our knowing, and God is also within our being. With that paradox, no wonder we keep building bridges that become boundaries – our bridges will never lead to the fullness of God. When we focus on the unknowableness of God, God becomes so mysterious and ineffable that God floats away like mist – how do we talk to mist? That’s unsatisfying, so we find tangible representations of God, in spiritual leaders or artifacts. Then, when God becomes so immediate and intimate, when God lives within us as humans, God can become the same as us and we face another trap – if we are God than does God exist? The Trinity is one answer to this conundrum – held within God is the elusive mystery of the Holy Spirit, and the intimate person of Jesus. Jesus brought God close through his own body, and even through his language. Jesus wasn’t the first person to call God “father,” but he made such a habit of it that “Father” has been a dominant metaphor for God ever since. The meaning we give the person of Jesus, the meaning we find in the name “Father” speak to our longing for an intimate connection with the mystery of God. Of course, the bridge of Jesus and the bridge of “Father God” are boundaries to many of us for all sorts of reasons. We will lose a lot when we reject a bridge – the familiar way of saying the Lord's Prayer or beloved hymns that use the name “Father.” But we are creative people and we adapt.... Remember when Jesus meets a Samaritan woman at the well in John chapter 4? That's a provocative story – Jesus and the woman break cultural taboos by talking across gender and culture. And they have a theological conversation. The woman says, " Our ancestors worshiped on this mountain, but you Jews claim that the place where we must worship is in Jerusalem.” Jesus replies, “believe me, a time is coming when you will worship God neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem....God is spirit, and those who worship God must worship in spirit and in truth.” And we read later in the book of John "the Spirit will guide us into all the truth." Isn't it interesting, that Jews and Samaritans were arguing over the right way to worship 2000 years ago, and today it seems pretty silly. Just think, 2000 years from now, what will people look back on our conflicts and shake their heads at? The altar changed over time in Judaism, just like it's been changing in Christianity. At one time the altar was against the wall (like it is here) and the priest put his back to the people as he performed sacred rituals on their behalf, often speaking a language they couldn’t understand, namely Latin. The people were bridged to God through this priest, even through the mystery and secrecy of the mass, but this set-up eventually became a boundary, and now priests face the people and usually speak a language they all understand. In many churches we’ve gone even further. We say in the Church of the Brethren that all members are ministers, and we often serve one another communion. Not only clergy come to our altar. And usually for Brethren, we share communion around the Love Feast table, absolutely communitizing communion. But our bridges, too, will become boundaries.... |

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed