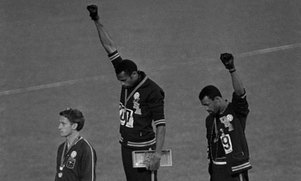

Peter Norman, Tommie Smith, John Carlos Peter Norman, Tommie Smith, John Carlos Hebrews 11:29-12:2 In my upbringing, competition, success, ambition were, if not dirty words, at least suspicious. Can any of you relate? The world's traditional values are turned upside down by Christianity. Jesus says over and over that the first will be last, and the last will be first. Brethren, particularly, cling to the Beatitudes, "blessed are the poor in spirit, blessed are the peacemakers, blessed are the meek." I grew up in a family and church that celebrated peacemakers more than Olympic gold medalists. I bet some of you did too. The athletes that did become heroes in my childhood were people like George Nicholas, a star runner, who refused to race for his university until the school changed its investments so it no longer profited from apartheid in South Africa. I learned about George Nicholas from the folk singer Charlie King, and the lyrics that tugged on my young heart, brought tears to my eyes, were these: “What have I got to lose? Scholarships, revenues. Maybe hang up these running shoes. But if I was a man in Johannesburg, I wouldn't get the chance to choose.” I did all sorts of sports growing up, but I never took them seriously. Changing the world, now that was serious business. So when an athlete like George Nicholas used his fame and athletic appeal to make the world a better place, that gave depth and purpose to sports beyond suspicious worldly values like winning and competition. The folk song goes on "All my life I've been trying for someone else's finish line. Well this time the race is mine. It may look like I'm just standing still, but inside I feel I'm flying." My heart raced with these words, I could picture myself on a state-of-the-art track in a huge stadium, the crowd filing in and spreading throughout the bleachers, and I imagined myself in George Nicholas’ skin, pacing in a track suit with no plans to hurry around that track. Even standing still, I trust his heart was racing. George Nicholas found a new race to run, a race that mattered to more than just himself or his team or his school. When we use our lives to witness to justice and compassion, we honor God. And often when we're witnessing to what matters most, it doesn't feel good, it's terribly hard, we can lose friends, we might lose sleep, we probably lose worldly success or wealth and we certainly lose comfort. And then we recall the Beatitudes, blessed are the persecuted, blessed are the poor in spirit. So when Paul writes (in our scripture from Hebrews) "let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us," I think of athletes like George Nicholas. He doesn't simply run the race that he'll win, he runs a race he might lose. He puts his ego, his status, completely on the line. He declares that he won't compete until his school divests from stocks that support apartheid in South Africa. What if his university chose their status quo over a few more track records? George Nicholas would look foolish, might have to transfer schools, might not be able to finish college, and would have nothing to show for it. That sounds like the kind of race that Paul says has been set before us. Leading up to that verse Paul recounts a history of faithful struggling – crossing the Red Sea to escape slavery, marching seven days around the walls of Jericho, Rahab risking her life and community to help the foreign Israelites. "And what more should I say?" writes Paul. "For time would fail me to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets— who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, obtained promises, shut the mouths of lions, quenched raging fire, escaped the edge of the sword, won strength out of weakness..." And he goes on several more verses about torture and flogging and execution. The stories Paul evokes are all about suffering, he gets pretty dramatic about it. We can get distracted by all the suffering and drama and I think it’s more important that we focus instead on the risk in each of these stories. The risk the Israelites took to leave the life they knew in Egypt and cross the Red Sea. The risk Rahab took to help foreign spies entering her city. Let’s read this passage from Hebrews as an invitation to run a risky race! Sometimes we will suffer, sometimes we won’t. I don't want to say that a faithful life is full of suffering and we should strive to be martyrs as often as possible - I think some Christians, especially Brethren, can get too invested in suffering and martyrdom out of pride, because we want to prove something about ourselves, prove how strong or faithful or selfless we are by how much we have suffered. Our egos speak up with ideas like that all the time, but our ego's voice is not the voice of God. So I'm not suggesting that we look around for struggle and strife and assume that's where God wants us to be. But a faithful life inevitably brings us into seasons of strife, down rocky roads, to races we'd rather not run at all. John Carlos and Tommie Smith, won gold and bronze medals on the US team in 1968. Their picture is in your bulletin. John Carlos and Tommie Smith trained harder than most of us can imagine for the 200 meter race they ran so well, so fast, that day. And still, that was the easier race they ran that day. John Carlos grew up in Harlem and was a natural athlete. He dreamed of swimming in the Olympics until his father broke the news that Olympic training pools were in private clubs that didn't allow black people. Perhaps he broke their hearts. Still, John Carlos was strong in body and spirit and he and his friends entertained themselves after school stealing food off freight trains and handing it out to poor and hungry people in Harlem. When the police chased them, John Carlos didn't get caught. (Younge, 2012) He trained for more than one race as he imperfectly chased justice for the meek, the poor in spirit, the hungry. Even though John Carlos prepared for the races set before him for years, the political statement he and Tommie Smith made at the 1968 Olympics was spontaneous. Certainly they didn't know they'd have the opportunity – they didn’t know they’d win and be on those pedestals. They’d just finished running 200 m faster than basically anyone else alive. They didn't have a specific plan. But they knew what mattered most. They weren’t planning, but they were prepared, to proclaim justice. "That's what I was born for," John Carlos said decades later. (Younge, 2012) I wonder what you feel when you see this picture – at the time, many white Americans were outraged. When I see this picture I see two people standing for justice, risking their safety and reputations, venturing into absolutely unknown territory with a new race to run. When I look at this picture my heart swells just like it does when I listen to the folk song about George Nicholas who refused to race until his university divested from apartheid: “What have I got to lose? Scholarships, revenues. Maybe hang up these running shoes. But if I was a man in Johannesburg, I wouldn't get the chance to choose.” John Carlos and Tommie Smith walked barefoot to receive their medals in solidarity with poor people around the world. When I look at John Carlos and Tommie Smith I see justice. But in 1968 many white people saw their hands raised in a black power salute and saw something scary, something disrespectful. Many in the crowd boo’ed. Many yelled “n-word, go back to Africa,” or “I can’t believe this is how you n-word treat us after we let you run in our games.” (Younge, 2012) I assume most white people didn’t feel that outraged, but most everyone was scared. 1968: Anti-Vietnam War sentiment rises as the Vietnam War kills record US soldiers. Richard Nixon and Eugene McCarthy and Bobby Kennedy run for president. US soldiers kill more than 500 civilians, from infants to the elderly, in Mi Lai. Martin Luther King is assassinated. 46 more people are killed during riots after his murder. Bobby Kennedy is assassinated. That’s just a taste from the first half of 1968, all months before these summer games in which John Carlos and Tommie Smith ran a race and raised their hands. It looks like justice to me, now, but I wonder what my grandparents thought at the time, they were in their 40s (not so much older than I am now). I wonder if they looked down on John Carlos and Tommie Smith as being too controversial, disrespectful, too confrontational. All the things that many concerned white people say today about Black Lives Matter protesters. What will future generations see in the pictures and hear in the stories from August 2016? When we suddenly realize that an unexpected race has been set before us, as John Carlos and Tommie Smith did in 1968, we might not run it perfectly. We might not convince anyone. We might not witness with finesse. That’s why we’re in training, today, for the opportunities we cannot predict. That’s why we practice our spiritual practices, that’s why we learn to speak with love, that’s why we listen more than we talk. As Richard Rohr says, “Those who agree to carry and love what God loves, both the good and the bad of human history, and to pay the price for its reconciliation within themselves—these are the followers of Jesus. They are the leaven, the salt, the remnant, the mustard seed that God can use to transform the world.” When we’re running the race that has been set before us, as Paul encourages in this passage from Hebrews, it means we don’t get to simply run the race we’d planned to run. It means we’re going to risk – we’re going to risk losing the prizes of pride and status and popularity. And when we run the holiest and most important races, we’re running before a “great cloud of witnesses.” Paul’s phrase is often considered to mean the saints and friends of the faith who have died and hover around in spirit to cheer us on as we do God’s work. But sometimes the great cloud of witnesses won’t cheer us on, sometimes they’ll boo. What was “great” about the cloud of witnesses as John Carlos and Tommie Smith received their Olympic medals was not their favor. What was great was that this crowd, this cloud of witnesses, needed to witness these men risking for justice. They needed to be shaken out of their white supremacist notion that they owned the Olympic games. “I can’t believe this is how you n-word treat us after we let you run in our games,” jeered some in the crowd. These spectators were talking to Olympic medalists, two of the fastest people alive. Whose Olympics? In 2016 the Olympics belong to 206 countries (Willis, 2016) and a team of refugees who are competing under the Olympic flag. When the modern international Olympic games began in the late 1800s, people hoped that countries competing in athletics would help them use up their aggression so they wouldn’t need to fight wars. Well, the Olympics invite just as much political controversy today as they did in 1968, or during the Nazi regime, or many other years of tension and war. This team of refugees is a first, and it’s about time, as this year the number of displaced people in the world has reached a record 65 million. (editorial, 2016) Who gets to be a team is absolutely controversial – can Taiwan have a team, or do they have to compete as China? Scotland or Great Britain? Palestine or Israel? Kosovo or Serbia? John Carlos and Tommie Smith joined the illustrious list of Olympic medalists at the 1968 games, and they also entered the hall of fame of athletes whose bodies and loyalties made political statements that ticked off people who just wanted to feel good about their country being the fastest and strongest. The 2016 Olympics belong to Yusra Mardini, who swam three hours through the sea to guide a lifeboat to Greece, keeping Syrian refugees like herself alive. Once she was discovered in a German refugee camp she started training for these Olympics in a pool built by the Nazi regime. What could be more political than a Syrian Muslim woman swimming in a formerly Nazi pool to prepare for these Olympic games? Yusra Mardini is 18 years old. She’s been swimming since she was 3; her dad coached swimming before their lives were overturned by war. For 15 years Yusra has been training for races she never could have predicted. The race put before her a year ago was swimming for her life through the Mediterranean Sea. Since then her race includes telling a new story about refugees – reminding the rest of the us that refugees aren’t simply victims to be cared for, but strong, fast, brave swimmers, too. With Yusra Mardini, with John Carlos, with Tommie Smith, with George Nicholas, we can proclaim “blessed are the peacemakers who run the race that is set before them.” Recall Richard Rohr’s words: “Those who agree to carry and love what God loves, both the good and the bad of human history, and to pay the price for its reconciliation within themselves—these are the followers of Jesus. They are the leaven, the salt, the remnant, the mustard seed that God can use to transform the world.” What race are you running today? We can run holy races whether we’re athletes or couch potatoes or in a wheelchair or have a heart condition. What race has caught you by surprise? Your career path, your college major, your serious hobby, your favorite sport – what have you been striving for that has taken you somewhere you never expected? Brought you into relationship with people who have transformed you. Opened a door you never would have sought? Taught you something invaluable about yourself? What race has been put before you that you will risk running? Who is your cloud of witnesses? Is it the audience you hoped for? Is it an audience that applauds and cheers? Or boos? Who is aching to witness you carry and love what God loves: justice, hope, compassion? “What does the Lord require of you?” asks the prophet Micah. Do justice, love kindness and walk humbly. This is training for any race set before us. We turn together to a hymn of this scripture, to set these words on our hearts, to train for the race. Benediction: Carry and love what God loves, as you run the race before you. The citations pasted strangely from Word. (editorial, 2016) is from Christian Century. Younge 2012: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/mar/30/black-power-salute-1968-olympics Willis, 2016: http://metro.co.uk/2016/08/12/how-many-countries-in-the-olympics-some-nations-wont-get-a-chance-at-glory-6063233/

0 Comments

Psalm 33:20-22 Matthew 7:7-8 1 Samuel 1:1-20 Psalm 33 says wait on God. Matthew 7 says knock and the door shall be answered. What's the deal? Is there a holy balance of waiting and knocking? Is it context-specific, or is there an ideal blend? Hannah's story offers one possibility. Hannah will not be stopped. Hannah waits for years for her first child. She waits alone. Hannah prays and plans, dreams and desires. Without her husband’s support, without the priest’s blessing, without change in her womb, Hannah will not be stopped. Hannah will not be shamed. Peninnah and Hannah are both married to Elkanah, Peninnah has children, and Hannah has Elkanah’s love. Though Hannah is the hero of this story and we relate to her, this situation would be painful for both women. Peninnah flaunts her children before Hannah. But Hannah will not be shamed. Hannah will not be soothed. Elkanah loves Hannah even though she has had no children. Though women of her time were primarily valued for their ability to give birth to sons, Elkanah has, perhaps, a progressive or passionate streak, and he loves Hannah anyway. Elkanah tells Hannah not to weep, not to grieve, but to be satisfied by his love. How can Elkanah be so indifferent to Hannah’s womb? Since he already has children with another wife, Elkanah can compartmentalize his own needs, and he's not concerned with Hannah’s fulfillment outside of their relationship to each another. He loves her, but he does not understand her sorrow, thinking extra portions from his temple sacrifices will satisfy her. But Hannah will not be soothed. Hannah will not be silenced. Year after year Hannah prays for a child. Years of waiting, years without signs, years without words of hope, do not dissuade her from praying, year after year, because Hannah’s desire for a child is so deep. She goes to the temple, even though, as a woman, she must stay on the edge. She does not allow this statement of her inferiority to silence her strong voice, but instead acts boldly on her own behalf. Hannah is audacious enough to make a bargain with God – “give me a son and I will give him back to you.” As Hannah speaks to God – mouthing her words because they are only intended for God – the priest Eli decides she must be drunk. Really?! It’s actually a pretty funny moment in scripture – what would you think if someone sat down in the pew next to you this morning, mouthing prayers and acting strange? Ironically, we don't expect that sort of behavior at church or temple. Eli misunderstands her spirit and shames her, tries to send her away. But Hannah, we're learning, is a bold soul, and she is not intimidated. She tenaciously responds, “Do not regard your servant as a worthless woman, for I have been speaking out of my great anxiety!” Hannah will not be silenced. Hannah’s story offers us one answer to the question posed by our scriptures today: do we wait on God, as the Psalmist sings, or do we knock, as Jesus preaches? Hannah does both. She is knocking throughout this story. She prays and plans, dreams and desires. She knocks and knocks, year after year. And Hannah waits on God, too, by finding peace before her prayers are answered. I'll say more about what I mean in a moment, but first I want to confess my deep discomfort with stories like this of Hannah, or Sarai or Rebekah or Rachel or any biblical woman whose story is about barrenness. There's a pattern to it, a couple doesn't get pregnant, the woman is considered barren, after a lot of prayer God opens her womb and they get pregnant and the story gets to be about God's power and mercy. So. What do you think and feel about these stories? I really want to know! If we were a small congregation I'd ask you to tell me right now, but we don't want to be up here while the youth's ice cream melts downstairs. So I'll tell you: these stories make me quite uncomfortable. I think they can be theologically dangerous, in fact. First reason: throughout scripture, infertility is always considered to be caused by a woman's barrenness. What modern science tells us is that about 10-15% of couples trying to get pregnant struggle with infertility. And in these couples, about 1/3 of the time the challenge is in the man's body, about 1/3 of the time the challenge is in the woman's body, and about 1/3 of the time it's a challenging combination in their bodies' interactions. So why do the women get all the blame? Now you might be thinking back on Abram and Sarai and recalling Hagar. You might think about Hannah and Elkanah and recall Penninah? These Old Testament men weren't expected to be monogamous, so we could read the stories at face value and think none of these men were infertile and their wives had all the problems, but I think the stories are simply a product of their times, including limited understanding of reproductive science. The other reason I think these stories are theologically dangerous is that they offer an oversimplified understanding of prayer and God's role in our lives. Because in each of these stories the whole point is that eventually prayers are answered and God changes infertility into fertility. Simple. Pray hard enough, be faithful enough, God will give you what you want. Knock on the door, the door opens, you see what you've been waiting for. But some of us have prayed to God for fertility, for healing from illness, for recovery from addiction, for our children's safety, for our spouse's forgiveness, for relief from depression, for a true love. We have prayed with every bit of our strength and faith for something clear and tangible. Some of us have celebration stories to share. And some of us have not gotten a simple, YES, answer to our prayers. Sometimes we knock and the door never opens. Sometimes we knock and when the door opens we're looking over a threshold we never expected and certainly didn't ask for. So are we not faithful enough? Not praying hard enough? This is why we read Hannah's story and learn from the peace she finds, the way she chooses to wait on God. When Hannah goes to pray, year after year, with no change in her womb, does she think about giving up? Even with her deep faith, she must doubt. Her culture and her family shame her for having no child, and she dares to hope anyway. She is a witness to any one of us who hopes for something that the world tells us we don’t deserve, or will never achieve. She must have moments of doubt and fear, but still, Hannah will not be stopped. It can be tempting to leave it all up to God, to say tragedy is “God’s will” or part of “God’s plan.” Now I do not believe that it is God’s plan for you to get fired, or be in a car accident, or have leukemia, or have a miscarriage. Yet God has created a world in which cycles of life and death permeate all existence, in which tragedy, brokenness and pain do occur. But God does not give someone cancer to have “another angel for the heavenly choir” or create a dysfunctional family to teach someone a valuable lesson. When we experience these sorrows, many of us wonder if God picked us for some divine reason. I don’t believe this is the way God moves in our lives, but I do believe that it is the divine spark within us that empowers us to respond to sorrow with strength, creativity, generosity, and extraordinary vision. Hannah does not passively wait on God to intervene, to bring her a child, or even to sustain her hope. Hannah claims her own divine power and joins God’s movement in the world, as she envisions a new reality, as she proclaims her heart’s longings. She doesn't keep secret her deepest desires, even when the world ridicules her. So Hannah cultivates hope rather than waiting for it to be given to her. She is knocking throughout this story. We hear in the story that after Hannah stands up for herself – not just to her husband and family, but even the priest Eli, her countenance is sad no longer. This all happens before she gets pregnant. She finds her way to peace before she has the outcome she’s been longing for. And then, paradoxically, a peaceful Hannah becomes a pregnant Hannah. Jesus says he came that we might have life abundant. Hannah lives an abundant life. Hannah will not be stopped, or shamed, or soothed or silenced. But let's rewind to Hannah's peace. Her countenance is sad no longer after she has proclaimed to her family, to the priest, to God, what she hopes for. And as Hannah honors her own self and her own need, she finds peace. While she is still NOT pregnant, Hannah finds peace. What is Hannah teaching us? Hannah is steadfast in her hope for a child – regardless of what was or wasn’t happening in her body, Hannah knows what she longs for and she isn’t ashamed to hold tight to her hope. What do you long for so much that you will dare to hope for it, even when the world around you thinks you’re a fool? Think about it now. We'll pause for a moment, really think about something that you are truly longing for today. Hannah surrenders to the movement and power of God in the world and within her. She is absolutely active in her praying and hoping and knocking yet she trusts the outcome is in God’s hands. Consider again what you’re longing for most fiercely – how can you surrender to God’s movement in your life? Pray and hope and knock with all your strength, and also let go of the outcome as you wait, peacefully, on God? I believe Hannah's wisdom speaks to us even if we don't hold her understanding of God, even if we don't see prayer the way she does. From what I read in the story, Hannah believes that if she prays to God, eventually God will give her what she's asking for. I bet a lot of us in this room think there's much more mystery involved. And still, Hannah's holy blend of knocking and waiting, of seeking and settling down, of reaching for and also resting, is wise for any of us. Let go and let God, it’s a cliché, but a good one. What does it mean to you? Do you believe the power of prayer means a blind person can regain sight? Someone’s cancer can be cured? But what about the praying person who still can’t see, who still has cancer, who never does get pregnant? Didn’t those people pray hard enough? When we've heard too much over-simplified, superficial religion, some of us give up on the whole package. But I invite you to keep the best of our faith tradition even as you let some parts go. I know there are some scientific studies that prove some power in prayer, but in our daily lives, prayer doesn't work the way turning on the faucet works. Just because we don't understand how praying and hoping and longing impact our lives, doesn't mean we have to give up on these mysteries. Hope is dangerous, isn’t it. What do you long for so fiercely that you’re willing to risk hope for it? Think about what you’re longing for, what you’re waiting for – if you got it tomorrow, if you woke up tomorrow and what you’re hoping for is here, how will you treat this new reality? Will you try to control it? Will you hold it tight? Maybe a week later, maybe a month later, might you be disappointed, that it’s not everything you’d been hoping it would be? Is parenting ever like that? Hannah couldn’t have hoped or prayed any harder for Samuel, then she gives him to the Temple, she only sees him once a year, she lets go of control over what she longed for more than anything else in the world. Pretty strange parenting by most of our standards, but she is a fulfilled mother, visiting him, making him priestly robes, telling stories of his growing taller and stronger. May we learn from Hannah about the abundant life that awaits each of us – even in sorrow, even in waiting – as she sees, with extraordinary vision, that which should not even be possible. And may we learn from Hannah about the abundant life that is always available to us as we learn to let go and let God move in our lives, in our hoping, and in our receiving. As we practice living abundantly, we turn to the image of the Kingdom of God. It is already, but not yet. It is a prayer not fully answered, but a miracle always available. Let us sing together Seek Ye First. ----- Benediction Go into the world this week boldly knocking and praying for what you long for, and find deep peace as lean in eagerly, waiting for the world to be right. |

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed